The recent move in the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield has garnered some interest and people are considering whether it’s a good time to diversify into bonds.

It’s an opportune time to talk through an assortment of principles about interest rates that should help you set your expectations in a way that leads to better decisions.

As we know, anything can happen in markets. Regardless of the wisdom of your choice, sometimes we get dealt 2-7 off-suit. This is the reality of markets and those of you who are able to ride the waves of variance while remaining calm and accepting your lot will continue making effective decisions into the future.

That’s why we focus on ideas that give us a good sense of the likely range of possibilities going forward. We aren’t trying to make a brilliant trade that catches the turn or get into the mega trend with perfect timing like a boss.

Of course, we would love to do that, but that’s not our expertise. From our perspective, it’s much more important to get the broad strokes right so that we do something reasonable and definitely good enough.

That’s because people who don’t do this for a living who aim to “time investments perfectly” have a habit of backdooring into the opposite of that. That’s the nature of markets.

Principle 1: The Market Gets what it Wants

The market sets interest rates. It’s very important that you understand this if you want to navigate interest rates effectively.

There are multiple manners in which this is true. Let’s start from a baseline principle.

Most people who read me know how price controls do not work. They create shortages, surpluses, and black markets.

People who understand prices know that prices are simply a communication mechanism which condenses a large amount of information about the world. When allowed to move freely, prices help goods and services move where they are highly valued.

A canonical example is how hotel prices rise greatly in a hurricane environment. This conveys information about supply to the entire world. It incentivizes families to cram themselves in where they otherwise wouldn’t. Because of this, people who really need immediate lodging are more able to find it.

Price controls are an attempt to stem the flow of information on what is supplied and what is demanded, with the typical result of creating dysfunction as long as they remain in place.

Usually governments eventually see they aren’t getting what they wanted out of the deal. This leads to reversion/over-shoot in the long run, as well as knock-on effects of adverse capital allocation.

Governments that persist with price controls observe the market in question going completely underground.1 Markets get what they want.

Very important principle. Markets get what they want over the medium to long term. That’s because markets represent the knowledge of all the people, and governments and policy makers are the tail wagged by the dog of all the people.

Policy makers can and do fight all the people at times, but they don’t do it for long. Inevitably, we see the market get what it wants.

Principle 2: Interest rates, growth, and inflation

Interest rates are, of course, just another price. They are the price of future money relative to present money. The market seeks an appropriate price of future money, and the market gets what it wants in the end.

As far as the 10-year rate goes, this is explicitly market-determined. There are central bank actions that tug this rate one way or another for a little while, which we can discuss in future articles.

You are best off having a good sense of the fundamental dynamic then assessing perturbations upon that dynamic on a case by case basis.

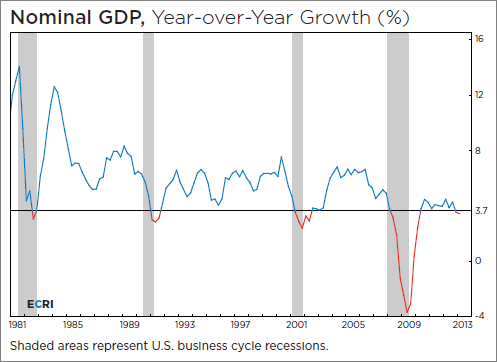

The 10-year rate has historically held at around the nominal growth rate of the economy. This is a shorthand which is easy to follow and intuitive.

If the market produces 6% more of dollar-denominated “stuff” into the next year, then it stands to reason that the “price” of a dollar from this year to the next will be something like 6% cheaper. That equalizes the proportion of all the “stuff” created that the same money can now acquire.

Indeed, this is generally what we see in the market of interest rates.

Thus, an increasing growth environment (like the last few years) coincides with higher rates. Similarly, an increasing inflation environment coincides with higher rates.

It’s the nominal production growth, or the sum of these quantities of real growth and inflation, that serves as an effective initial heuristic for the overall rate level.

Notably, real growth is a residual of nominal growth minus inflation. Since inflation can be quite volatile, it’s often best to focus on nominal growth, whose year over year measurements are more stable.

Alterations in the overall trajectory of nominal growth are highly influenced by features like demographic change and technological development (which feeds into productivity).

When we characterize it in this way it becomes quite easy to see why policy makers are the tail on the dog of the rates market. The market gets what it wants. The Fed doesn’t have tools to effect outlandish demographic change.

Their hands are a lot more tied than many think they are.

If you would like to delve into more detail on this, you can study esteemed Professor Aswath Damodaran’s excellent breakdown here.

The better you understand this, the better you are equipped to anticipate the reasonable range of interest rates going forward.

When the Fed fights the market

The Fed does control a short term interest rate: an inter-bank lending rate known as the Fed Funds rate. The Fed funds rate impacts the economy through the short-term credit channel.

The Fed’s policy rate has significant impact on the level of rates from 3-month Treasury bills to Treasury bonds of 2-year duration. This span is commonly referred to as the “short end” of the yield curve.

Since it’s tempting to believe that this is sufficient for the Fed to play god with the markets, I’m going to describe to you how the market forces the Fed to heel, with historical examples.

One way the Fed could fight the market is if nominal growth levels are high, the market wants rates to be high, and the Fed obstinately keeps the short end low despite this.

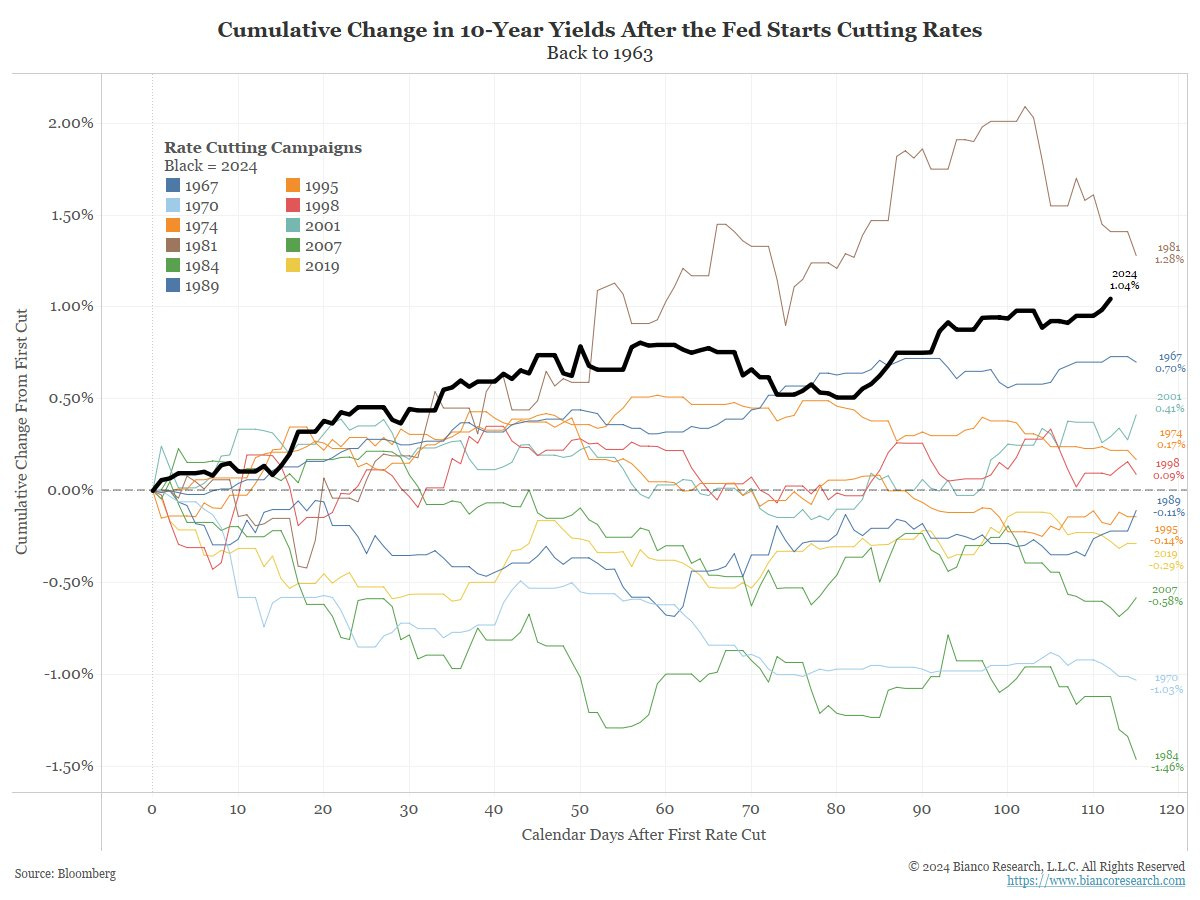

This is something we saw in 1981-1982 with Volcker and is quite similar to what we have now.

In this scenario you observe the Fed lower rates at the end that it has direct control over: the short end. As the Fed does this, the long end, the 10-year to 30-year duration region, moves dramatically higher in yields.

The market puts it upon itself to “right” the Fed’s “wrong.”

Here’s how you can conceptualize this as a narrative. The nominal growth rate of the economy is “hot” or high, so the percentage growth of production is doing great. This often comes with inflation, which is not so great.

The Fed uses its policy lever to create a short rate that doesn’t reflect the economy that it is actually dealing with. The Fed’s rate is too low.

Lower Fed funds rate stimulates the economy: it throws more gas onto a fire that’s already burning brightly.

The market sees a Fed that is not serious about managing the inflationary consequences of too much of a good thing, and sends rates higher. Stimulating a rapidly growing nominal economy means we should expect even greater things ahead.

Higher nominal growth conditions means higher 10-year yields.

If nominal growth expectations rise quickly, the bond market sell-off can become disorderly (a rise in rates is a fall in bond price). This is very much not what policy makers want.

Disorderly markets create job risk for policymakers. They often put strain on large and powerful institutions like banks and pension funds, who have the influence to demand a change.2

In scenarios like this, the market brings the Fed to heel. Volcker did a swift U-turn, bringing the Fed funds rate back up, following the market and giving the market what it wanted. Policymakers can fight conditions for a little while, but once things get disorderly, the market gets what it wants.

It’s important to understand that the “right rate” depends on the economic conditions, and can be much higher or lower depending on demographic dynamics.

It can be much higher or lower in different time periods or in different countries. For example, Japan’s rate remains near the lower bound even as the US short term rate has risen rapidly from near 0% to around 5%. That’s because the U.S. has much higher nominal growth than Japan.

They don’t have the same “right rate.” The market wants different things in these places, and the market gets what it wants.

The Fed might have to do a bit of experimenting to figure out what the market wants, but it eventually figures it out in time. That or its members enjoy new employment as the government finds people who are willing to figure it out and capable of doing so.

The inverse of this situation would be a scenario where the Fed obstinately restricts credit to the market when growth and inflation are quite low, which threatens to create the dreaded “deflationary spiral,” where deleveraging feeds upon itself.

This is best known historically among Americans through the Great Depression, and the consequences of this remain so strongly felt that the low nominal growth period of 2008 to 2020 was met by central bankers eager to do anything they could think of to allay such an outcome.

This is how we saw zero and even negative interest rates in places, as well as quantitative easing to further stimulate markets that threatened to slow in a disorderly way.

Yet again, it’s important to recognize that the market wanted low rates, and brought central bankers to heel. The Global Financial Crisis created a large deleveraging across financial markets, which is a strong disinflationary process (nominal growth down).

Further, globalization concordant with the industrialization of China created another strong disinflationary impulse: the last couple of decades have created a market environment that wants low rates, and it got them. The market gets what it wants.

Principle 3: Know Our History

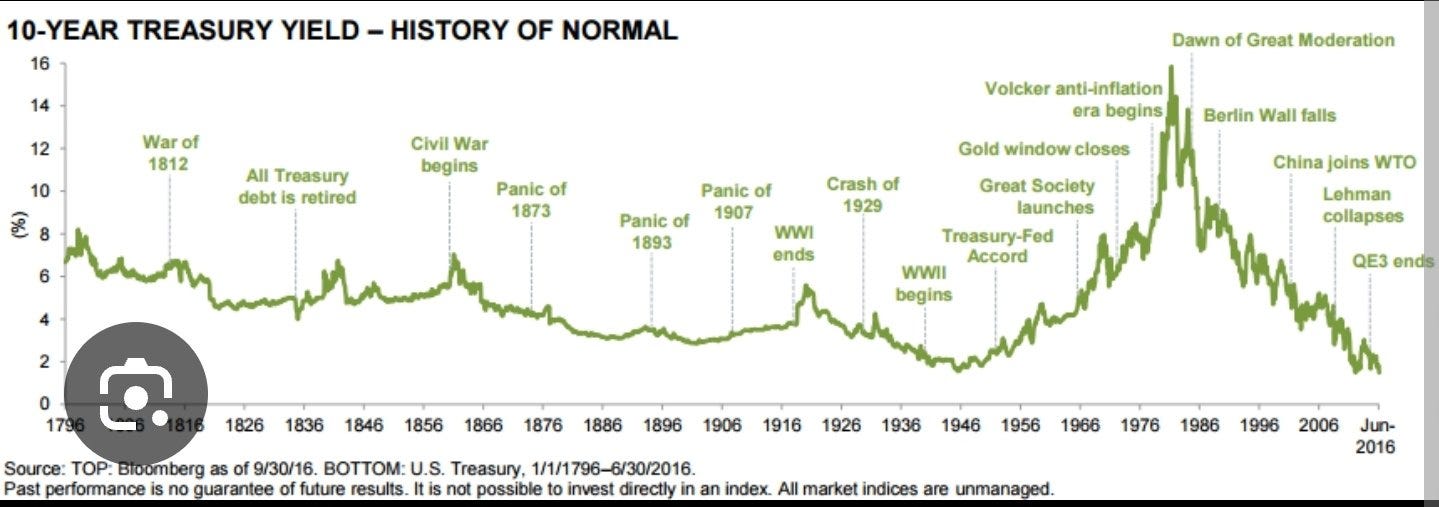

Here’s the 10 year rate for the last few centuries.

Currently the 10-year rate is around 4.5%, which, if you bring it into the wider context of history, is a very normal interest rate. Nothing out of the ordinary. It’s near the historical average. If we picked a time period at random from the historical record, we’d expect to get something like this.

It’s helpful to have a good sense of our history of interest rates because the last couple of decades are incredibly anomalous when put into perspective.

People who don’t take the time to examine history more closely are liable to assume that their life experience determines what is normal. Scientists call this “bias” but honestly it’s intelligent: it makes sense to assume that the world will keep doing what it has shown you all your life.

Nevertheless, this represents an opportunity for students of history. Sometimes cool things happen, and it’s worth knowing that an unusual situation might not be as typical as others expect. It helps you set effective expectations going forward.

Let’s zoom in a bit.

I think you can see the danger that might arise from assuming your life experience tells you what will happen going forward every time.

Many of my readers have a “market lifetime” contained entirely within the box. In the grand scheme of things, the box is quite a wonderful and unique period.

To put it into the appropriate context, we first understand that the market dictates to the Fed what interest rate it desires, based on nominal growth conditions, and the market ultimately gets what it wants.

I am flexible and adaptive

Post Global Financial Crisis you had a situation where banks did not have ample capacity to extend credit; they were undergoing an extended period of deleveraging to repair balance sheets. That’s a downward force on nominal growth. Those balance sheets have been repaired at this point, opening the credit channel and reversing this core driver.

Second, the integration of China’s production into free trade markets led to a large supply increase in industrial production, which helps keep overall price levels low and therefore does the same to inflation and nominal growth.

This has been in the process of leveling out and reversing for some time. Its current newsworthy iteration is discussion of tariffs, on-shoring, and “near”-shoring of industrial capacity due to Trump’s desired policies.

It’s important to recognize that Trump is responsive to the desires of the public. Brexit is another example of this phenomenon, and shows how it is global.

Politicians can and do try to override the people in favor of the status quo, but just as the market eventually gets what it wants, the people eventually get what they want. It’s sledding uphill to try to go against all the people. Splintering free trade agreements is popular: one reason why this trend is referred to as “Populist.”

Aspiring figures of power who, like Trump, prove they are capable of adapting with the times, find themselves winning landslides. If your goal is to make the most money in your investing, you focus away from whether these trends are “good” or “right” so you are equipped to respond to them as they happen.

You see them for what they are, and improve your decisions accordingly. The world is dramatically changing all the time, and if you understand that key features of the world will continue to change forever, you successfully ride the wave as others get sucked into the undertow.

Finally, there is a major demographic shift as large cohorts of Boomers and millenials move into new stages of their lives. Previously, Boomers were in asset accumulation mode as they approached retirement, but did not yet reach it.

Now, Boomers are dissaving assets, strengthening nominal growth where before their saving reduced nominal growth. Further, millenials are moving into household formation with higher spending needs.

All of this is effectively stimulative to nominal growth, and essentially set in stone barring surprising and historically rare demographic shifts resulting from mass death. Those who want to explore further can read this excellent piece by Danny Dayan.

The synthesis is that nominal growth helps us understand what the market wants when it comes to interest rates, and most of the key drivers that have kept this chart so low in the last couple of decades are reversing. That reversal process is likely to continue.

We will see it expressed in interest rates if we are appropriately zoomed out and not putting too much stock in quarter-to-quarter wiggles.

Currently, the Fed remains somewhat anchored to the “market lifetime” of its members (the “box”). The Fed consistently lowers its policy rate below what is appropriate in these new and exciting conditions. Which is why we are seeing the bond market not cooperate. It has decided it will gift higher yields to the Fed no matter what the Fed does.

If the bond market becomes disorderly, I expect the Fed to get the message quickly, and respond accordingly. The market always has the tools to get what it wants from policymakers who can’t see reason with sufficient alacrity.

Not only does the box represent an abnormally low interest rate historically, the macroeconomic drivers of rates tell us that this remarkable period is not likely to sustain going forward.

On the contrary, it appears that snap-back is in the offing. We aren’t in Kansas anymore.

Interest Rates: Am I Excited to own Bonds?

All of this helps us consider whether it’s a good time to sell other assets to own bonds. After all, with higher yields, they certainly look more appealing than before.

It’s worth thinking about.

On the other hand, if even further and higher yields are coming in the future, that represents lower bond prices, so that would not be good for our investing outlook if we are putting a large amount of capital into bonds.

This principles primer gives us a good big picture on the drivers of interest rates and a reasonable set of expectations going forward. We want to have an effective sense of what could happen broadly, because getting things “mostly right” in markets is exactly where we want to be.

The best insight many will get from this outlook is why it’s smart to reset the feeling that these rates are “too good to be true.” Price is almost always where it is for good reasons.

Understand those reasons well, and you stay on track to getting things “mostly right.” It might not be the most exciting to conclude that both 2% up and 2% down in rates from here are reasonable, but it sure beats getting it totally wrong out of ignorance.

The usual key principle is when we are not in markets 24/7, we understand we don’t have a good read on what exactly will happen soon. Positioning flexibly and for the long-term tends to give us the best chances.

I don’t typically write articles like this, so feedback is highly encouraged and appreciated, especially if you think it could lead to further informative writings.

I look forward to your future rapid rises.

Those of you who are familiar with private credit can think about how it represents another example of the market getting what it wants. The Global Financial Crisis understandably created regulatory restrictions on banking actions. The market still wants higher-yield credit channels. The market finds a way.

Folks who want more historical examples of this can look into Great Britain’s “Liz Truss moment.” Policy decisions instigated a disorderly sell-off in the gilt market (British bonds), which put strain on pensions funds associated with LDI (liability-driven investment). The market forced policymakers to adapt. The market gets what it wants in the end.

Great article. Not too long and has good info. Love your writing!! 💛💛

Very interesting. I will probaly have to re read it a couple of times and take notes.